Operations Plan

Historical Military Strategy Document

CLASSIFICATION: Unsolved Homicide

LOCATION

Argentina

TIME PERIOD

1810

VICTIMS

0 confirmed

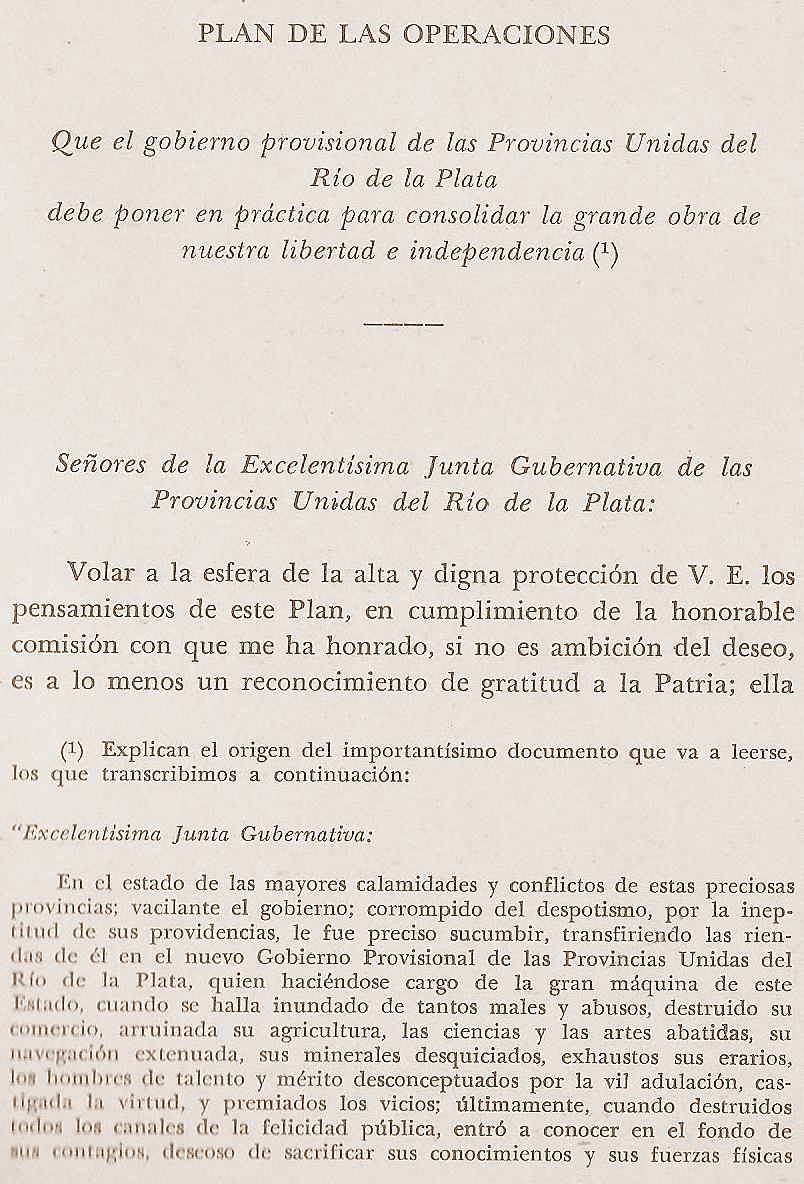

On August 31, 1810, a secret operations plan attributed to Mariano Moreno was proposed to the Primera Junta, the first de facto independent government of Argentina, during a critical meeting with notable figures including Manuel Belgrano and Juan José Castelli. The document outlines aggressive strategies aimed at defeating royalist forces, advocating for actions reminiscent of the Jacobins during the French Revolution, and categorizing the population into loyalists, enemies, and neutrals. It emphasizes the need for a robust espionage network to monitor and punish royalists, including execution for influential opponents, while promoting loyalists to key positions within the government. The authenticity of the document remains contested among historians, with some viewing it as a genuine historical artifact and others as a literary forgery. The current status of the document is that it remains a subject of academic debate, with no definitive resolution regarding its legitimacy.

Historians are divided on the authenticity of the Operations plan attributed to Mariano Moreno; some believe it to be a genuine historical document, while others argue it is a literary forgery. Those who support its authenticity theorize that the plan was a response to the revolutionary climate of the time, aiming to outline aggressive actions against royalist forces similar to those of the Jacobins during the French Revolution. The document's rejection of political moderation suggests a belief that decisive and extreme measures were necessary for the success of the independence movement.

The Operations Plan: A Secret Blueprint for Revolution

In the tumultuous dawn of the 19th century, as Argentina wrestled with its colonial chains, a clandestine document, known as the Operations Plan, emerged from the shadows. It was a blueprint for revolution, attributed to Mariano Moreno, a key figure in Argentina's first de facto independent government, the Primera Junta. This document, shrouded in secrecy and controversy, outlined the harsh measures necessary to secure the Junta's goals. While some historians dismiss it as a literary forgery, others believe in its authenticity, seeing it as a vital instrument in Argentina's struggle for independence.

Creation and Purpose

According to those who consider the document genuine, its creation was prompted by a meeting between Mariano Moreno, Manuel Belgrano, and Juan José Castelli. The latter two allegedly urged Moreno to draft this plan, which he presented to the entire Junta by August 31, 1810. The Operations Plan was intended as a covert government platform, laying out strategies to defeat royalist forces and secure independence from Spanish rule.

Revolutionary Tactics

Actions Against Royalists

In the context of the Argentine War of Independence, Moreno's plan drew inspiration from the Jacobins' tactics during the French Revolution's Reign of Terror. He eschewed political moderation, viewing it as perilous in revolutionary times. The document categorized the populace into three groups: loyals, open enemies, and neutrals. Loyals were to be rewarded with privileges and state offices, though promotions were to be cautious and calculated. In contrast, Peninsulars—Spaniards residing in Argentina—were to be closely monitored and severely punished for any anti-Junta activities, with executions reserved for those of wealth or influence.

To achieve these ends, Moreno proposed establishing an espionage network and executing top military and political adversaries. The plan also advocated for manipulating the press to favor the government and suppress detrimental news.

Moreno foresaw the difficulty of a blockade against Montevideo due to its naval superiority and instead suggested garnering support from nearby smaller towns. He recognized the strategic value of potential allies like José Gervasio Artigas and José Rondeau, urging Buenos Aires to enlist their aid against absolutism. Upon capturing Montevideo, Moreno proposed confiscating royalist assets and banishing or drafting those unable to prove their loyalty.

The plan extended its revolutionary ambitions beyond Argentina, urging support for local patriots against royalists in Chile and Paraguay. It also contained abolitionist elements, advocating for the end of the slave trade and the emancipation of slaves with Spanish masters, while enlisting them into militias with the promise of freedom after service.

International Relations

On the international stage, Moreno rejected Brazilian slavery, proposing the circulation of libertarian ideas through translations of the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres and military support for potential slave uprisings. He identified Britain as a potential ally against the threats of Spanish absolutism or complete defeat in the Peninsular War, valuing British arms and goods but cautioning against excessive British influence in Argentina's economy.

Regarding Spain, Moreno advised delaying a declaration of independence until the revolution gained strength and the Peninsular War's outcome became clear. He suggested maintaining a facade of loyalty to Ferdinand VII to ease international relations and create confusion about which side was truly loyal to the king.

Economic Strategies

The Operations Plan addressed the lack of a bourgeoisie to drive economic development, advocating for strong state intervention. Moreno proposed significant state investment in factories, agriculture, and navigation, funded by nationalizing Potosi's lucrative mines. This economic strategy aimed to create self-reliance, with the state gradually relinquishing control once robust economic activity was established.

Moreno's economic vision included protectionist policies, such as high tariffs on luxury imports, contrasting with his earlier advocacy for trade with Britain. He reduced export tariffs but maintained high import tariffs, which were only lifted during the First Triumvirate years later.

Controversy and Authorship

The Operations Plan's authenticity has been hotly debated. Its first copy was discovered in the Archives of the Indias in Sevilla by Eduardo Madero, who sent it to Argentina, where Bartolomé Mitre misplaced it. A second copy was found by Norberto Piñeiro, who published it instead of sending it back. Critics like Paul Groussac and Ricardo Levene accused the document of being a forgery, possibly penned by an opponent to discredit the revolution. Levene argued that the handwriting belonged to Andrés Álvarez de Toledo, not Moreno.

Supporters contend that the document was a copy, not the original, and that its handwriting by another individual was not unexpected. Despite no contemporary references to the plan by Junta members, Enrique Ruiz Guiñazú published letters from Carlota Joaquina and Ferdinand VII that referenced Moreno's plan, supporting its authenticity.

Some authors question Moreno's sole authorship, suggesting Manuel Belgrano or Hipólito Vieytes may have contributed. Norberto Galasso posits a collaborative creation, with Moreno as the primary author.

Sources

For further reading, the original Wikipedia article can be found here.

No Recent News

No recent news articles found for this case. Check back later for updates.

No Evidence Submitted

No evidence found for this case. Be the first to submit evidence in the comments below.

Join the discussion

Loading comments...

On August 31, 1810, a secret operations plan attributed to Mariano Moreno was proposed to the Primera Junta, the first de facto independent government of Argentina, during a critical meeting with notable figures including Manuel Belgrano and Juan José Castelli. The document outlines aggressive strategies aimed at defeating royalist forces, advocating for actions reminiscent of the Jacobins during the French Revolution, and categorizing the population into loyalists, enemies, and neutrals. It emphasizes the need for a robust espionage network to monitor and punish royalists, including execution for influential opponents, while promoting loyalists to key positions within the government. The authenticity of the document remains contested among historians, with some viewing it as a genuine historical artifact and others as a literary forgery. The current status of the document is that it remains a subject of academic debate, with no definitive resolution regarding its legitimacy.

Historians are divided on the authenticity of the Operations plan attributed to Mariano Moreno; some believe it to be a genuine historical document, while others argue it is a literary forgery. Those who support its authenticity theorize that the plan was a response to the revolutionary climate of the time, aiming to outline aggressive actions against royalist forces similar to those of the Jacobins during the French Revolution. The document's rejection of political moderation suggests a belief that decisive and extreme measures were necessary for the success of the independence movement.

The Operations Plan: A Secret Blueprint for Revolution

In the tumultuous dawn of the 19th century, as Argentina wrestled with its colonial chains, a clandestine document, known as the Operations Plan, emerged from the shadows. It was a blueprint for revolution, attributed to Mariano Moreno, a key figure in Argentina's first de facto independent government, the Primera Junta. This document, shrouded in secrecy and controversy, outlined the harsh measures necessary to secure the Junta's goals. While some historians dismiss it as a literary forgery, others believe in its authenticity, seeing it as a vital instrument in Argentina's struggle for independence.

Creation and Purpose

According to those who consider the document genuine, its creation was prompted by a meeting between Mariano Moreno, Manuel Belgrano, and Juan José Castelli. The latter two allegedly urged Moreno to draft this plan, which he presented to the entire Junta by August 31, 1810. The Operations Plan was intended as a covert government platform, laying out strategies to defeat royalist forces and secure independence from Spanish rule.

Revolutionary Tactics

Actions Against Royalists

In the context of the Argentine War of Independence, Moreno's plan drew inspiration from the Jacobins' tactics during the French Revolution's Reign of Terror. He eschewed political moderation, viewing it as perilous in revolutionary times. The document categorized the populace into three groups: loyals, open enemies, and neutrals. Loyals were to be rewarded with privileges and state offices, though promotions were to be cautious and calculated. In contrast, Peninsulars—Spaniards residing in Argentina—were to be closely monitored and severely punished for any anti-Junta activities, with executions reserved for those of wealth or influence.

To achieve these ends, Moreno proposed establishing an espionage network and executing top military and political adversaries. The plan also advocated for manipulating the press to favor the government and suppress detrimental news.

Moreno foresaw the difficulty of a blockade against Montevideo due to its naval superiority and instead suggested garnering support from nearby smaller towns. He recognized the strategic value of potential allies like José Gervasio Artigas and José Rondeau, urging Buenos Aires to enlist their aid against absolutism. Upon capturing Montevideo, Moreno proposed confiscating royalist assets and banishing or drafting those unable to prove their loyalty.

The plan extended its revolutionary ambitions beyond Argentina, urging support for local patriots against royalists in Chile and Paraguay. It also contained abolitionist elements, advocating for the end of the slave trade and the emancipation of slaves with Spanish masters, while enlisting them into militias with the promise of freedom after service.

International Relations

On the international stage, Moreno rejected Brazilian slavery, proposing the circulation of libertarian ideas through translations of the Gazeta de Buenos Ayres and military support for potential slave uprisings. He identified Britain as a potential ally against the threats of Spanish absolutism or complete defeat in the Peninsular War, valuing British arms and goods but cautioning against excessive British influence in Argentina's economy.

Regarding Spain, Moreno advised delaying a declaration of independence until the revolution gained strength and the Peninsular War's outcome became clear. He suggested maintaining a facade of loyalty to Ferdinand VII to ease international relations and create confusion about which side was truly loyal to the king.

Economic Strategies

The Operations Plan addressed the lack of a bourgeoisie to drive economic development, advocating for strong state intervention. Moreno proposed significant state investment in factories, agriculture, and navigation, funded by nationalizing Potosi's lucrative mines. This economic strategy aimed to create self-reliance, with the state gradually relinquishing control once robust economic activity was established.

Moreno's economic vision included protectionist policies, such as high tariffs on luxury imports, contrasting with his earlier advocacy for trade with Britain. He reduced export tariffs but maintained high import tariffs, which were only lifted during the First Triumvirate years later.

Controversy and Authorship

The Operations Plan's authenticity has been hotly debated. Its first copy was discovered in the Archives of the Indias in Sevilla by Eduardo Madero, who sent it to Argentina, where Bartolomé Mitre misplaced it. A second copy was found by Norberto Piñeiro, who published it instead of sending it back. Critics like Paul Groussac and Ricardo Levene accused the document of being a forgery, possibly penned by an opponent to discredit the revolution. Levene argued that the handwriting belonged to Andrés Álvarez de Toledo, not Moreno.

Supporters contend that the document was a copy, not the original, and that its handwriting by another individual was not unexpected. Despite no contemporary references to the plan by Junta members, Enrique Ruiz Guiñazú published letters from Carlota Joaquina and Ferdinand VII that referenced Moreno's plan, supporting its authenticity.

Some authors question Moreno's sole authorship, suggesting Manuel Belgrano or Hipólito Vieytes may have contributed. Norberto Galasso posits a collaborative creation, with Moreno as the primary author.

Sources

For further reading, the original Wikipedia article can be found here.

No Recent News

No recent news articles found for this case. Check back later for updates.

No Evidence Submitted

No evidence found for this case. Be the first to submit evidence in the comments below.

Join the discussion

Loading comments...